The evolving airspace ecosystem

How to replace human eyes to keep our national airspace safe

Imagine a world where drones deliver emergency medical supplies to people in need. Or shuttle commuters from place to place avoiding ground traffic and breaking down the geographical divide between cities and suburbs.

Autonomous drones could spray pesticides on crops, monitor construction sites, or film adventure seekers skiing down mountains.

Potential drone applications are limited only by our imaginations… and our ability to operate them safely.

Right now the FAA is working together with the tech industry to build new rules of engagement to ensure that these unmanned aerial vehicles avoid a collision without the eyes of human pilots.

These regulatory hurdles are the last obstacle to letting the market for autonomous drones soar.

Image of Impossible Aerospace US-1

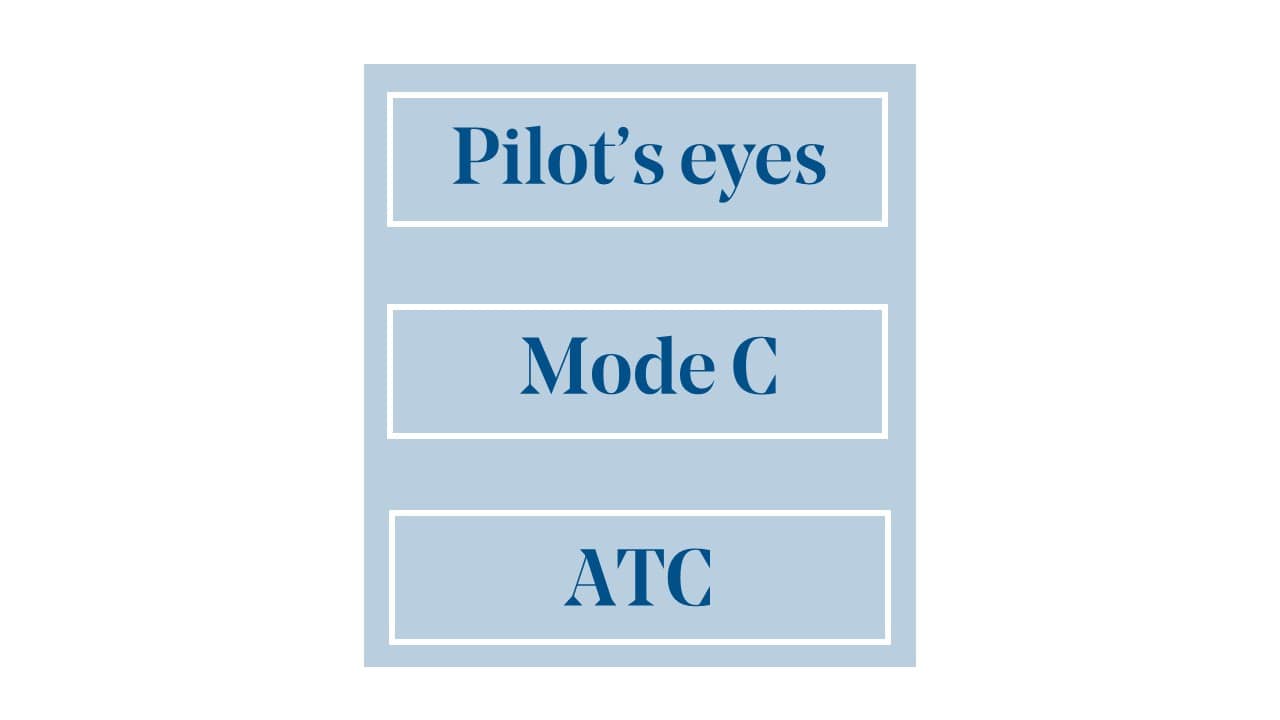

The current airspace ecosystem

Aircraft, from Cessna 152s to Airbus 380s, are the most common vehicles that populate and cruise the airspace. And they all require a pilot’s eyes to operate.

In the case of commercial aircraft, they also require a Mode C Transponder, which determines the aircraft’s altitude. All commercial and most private aircraft also have to communicate with Air Traffic Control (ATC), people on the ground who logistically coordinate which aircraft taxi, take off, and land at airports.

This is a system with three layers of protection and vigilance to avoid horrific and often fatal crashes: ATC, Mode C, and the pilot’s eyes. With unmanned aircraft, this universally accepted system for keeping the National Airspace System safe will have to change.

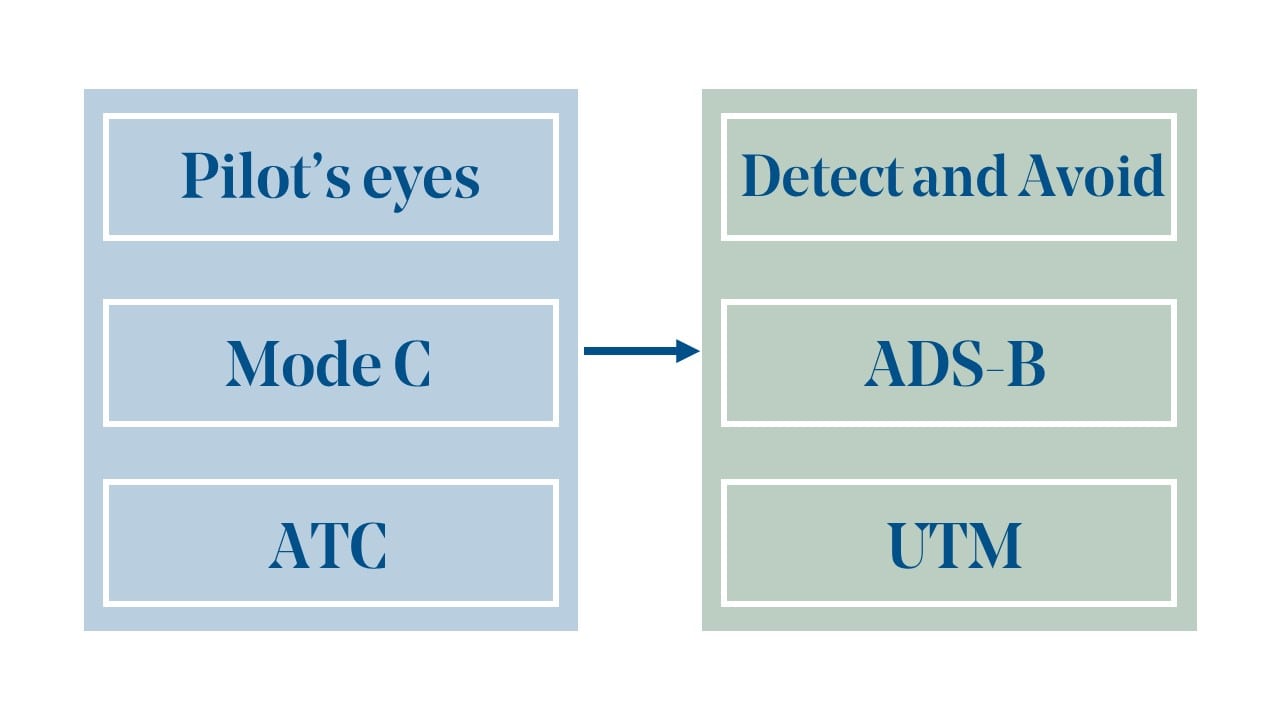

Digitizing the airspace for drones flown by artificial intelligence

Objects that don’t have humans on board can’t use eyes to avoid collision, or communicate and listen to ATC. As a substitute for humans and eyes, these vehicles must rely on several new systems, largely using artificial intelligence. And these systems will require that the current ecosystem operate digitally in real time.

In the very near future, Unmanned Traffic Management (UTM) hopes to seamlessly integrate with today’s version of ATC.

UTM strives for the digital sharing of each user’s planned flight details with the goal for each user (e.g. “pilot”) to have the same situational awareness of the airspace. That way, as drones navigate the skies they will know whether or not they’re impeding any other traffic in the sky. Companies like Airmap and Unifly are working on such systems. While UTM is a great idea, it’s hard to standardize such a system because it will be nearly impossible to convince or require 100 percent of manned pilots to use it. There will always be non-cooperative aircraft, just like there will always be automobile drivers who do not wear their seat belts even though the benefits of doing so are obvious and compelling.

Therefore, we will need to aggregate other layers of safety on top of UTM to ensure our airspace is safe. Specifically, the Mode C Transponder will be updated to an Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) sensor. This enhanced sensor transmits aircraft-to-aircraft and provides significant additional real-time precision to help both pilots and controllers achieve shared situational awareness.

As the last critical layer of safety and redundancy, if for whatever reason a manned aircraft pilot doesn’t enter her flight path in the UTM system or the aircraft doesn’t have a working ADS-B sensor, both common scenarios, the drone needs to have an equivalent to the pilot’s eyes to avoid another flying object.

Bessemer portfolio company, Iris Automation has developed a system that provides drones with eyes in the sky. The system uses a small module with a camera that feeds into a real-time, onboard computer vision and deep learning algorithm to detect, track, classify, and if needed, avoid, other objects in the airspace to keep the drone safe throughout its flight.

At present, Iris is the only company with an FAA beyond visual line-of-sight (BVLOS) waiver and is the only certified detect and avoid (DAA) system in the market. The BVLOS system doesn’t require a visual observer on the ground and the entire system fits into the palm of your hand, weighing only 350 grams.

The wild blue yonder of drone ubiquity

One day drones will ubiquitously operate in our airspace preventing disasters and making our lives safer, easier, and better. They’ll put out fires, deliver late night take out, and inspect our infrastructures such as bridges, railways, and pipelines.

In order for all this to happen, it will be necessary for pilots, drone users, manufacturers, and the FAA to embrace and use this new digital technology and ecosystem. When they do, the virtually endless possibilities associated with drone technology can be realized in a way that will make the skies even safer.