Six CEO lessons to help your ‘teenage startup’ thrive

Scaling a company? Expect everything to change. Here are six ways you need to adapt your leadership to thrive as your company scales.

If you’re a CEO responsible for scaling a business into double-digit ARR, chances are it’s your first time. Very few growth-stage CEOs have the benefit of experience when they rise to this daunting challenge. So it’s natural to feel a huge weight of responsibility on your shoulders—to employees (and their families), to your management team, to investors and your Board, and to yourself. And, yet, at the same time, there’s no guidebook to prepare you for the one-of-a-kind challenge of scaling your particular business. The next best thing, however, is talking to folks who have done it before.

That’s why I wanted to write this guide—to share the surprises I encountered to prepare you for your startup’s “teenage years.” And while I recognize that every situation is unique, and my lessons learned may not map one-to-one to yours, I do hope that some of the generalized lessons here will prove useful.

When I joined SendGrid in 2014, it was a ~$30 million dollar business with 150 employees and big ambitions to grow to over $100 million (what we now call a Centaur) and go public within three to four years. By the time I left in 2020, we had scaled to over 400 employees, had taken the company public, then got acquired by Twilio, all while building from a business with tens of millions of ARR to one with hundreds. The number one question fellow CEOs on the same journey would often ask was, “What changes when you grow a business past $10M ARR?” My answer? Nearly everything.

The way you lead when you're going from zero to $1 million in ARR is wildly different from $1 million to $10 million, which in turn is wildly different from $10 million to $100 million. When you get out of startup mode and move into the growth stage, your approach must change radically if you’re going to continue to be an effective leader. You have to let go of the tactics that led to your success to date because they're often directly contradictory to what you need to be doing for the next stage. The adage “what got you here won’t get you there” is particularly poignant here.

One note before we dive into the lessons I learned: I encourage you to read on with a very open mindset and remember that new business goals require different leadership skill sets. Humans brains have evolved to be very comfortable with routine. We are resistant to meaningful changes. Unfortunately as you are building a company, for every next summit you ascend, everything is going to change. The sooner you can welcome change, the better of a leader you’ll be.

Read on as I share six radical changes you need to make to your leadership style to remain successful as you scale from double-digit ARR to triple-digit ARR and beyond.

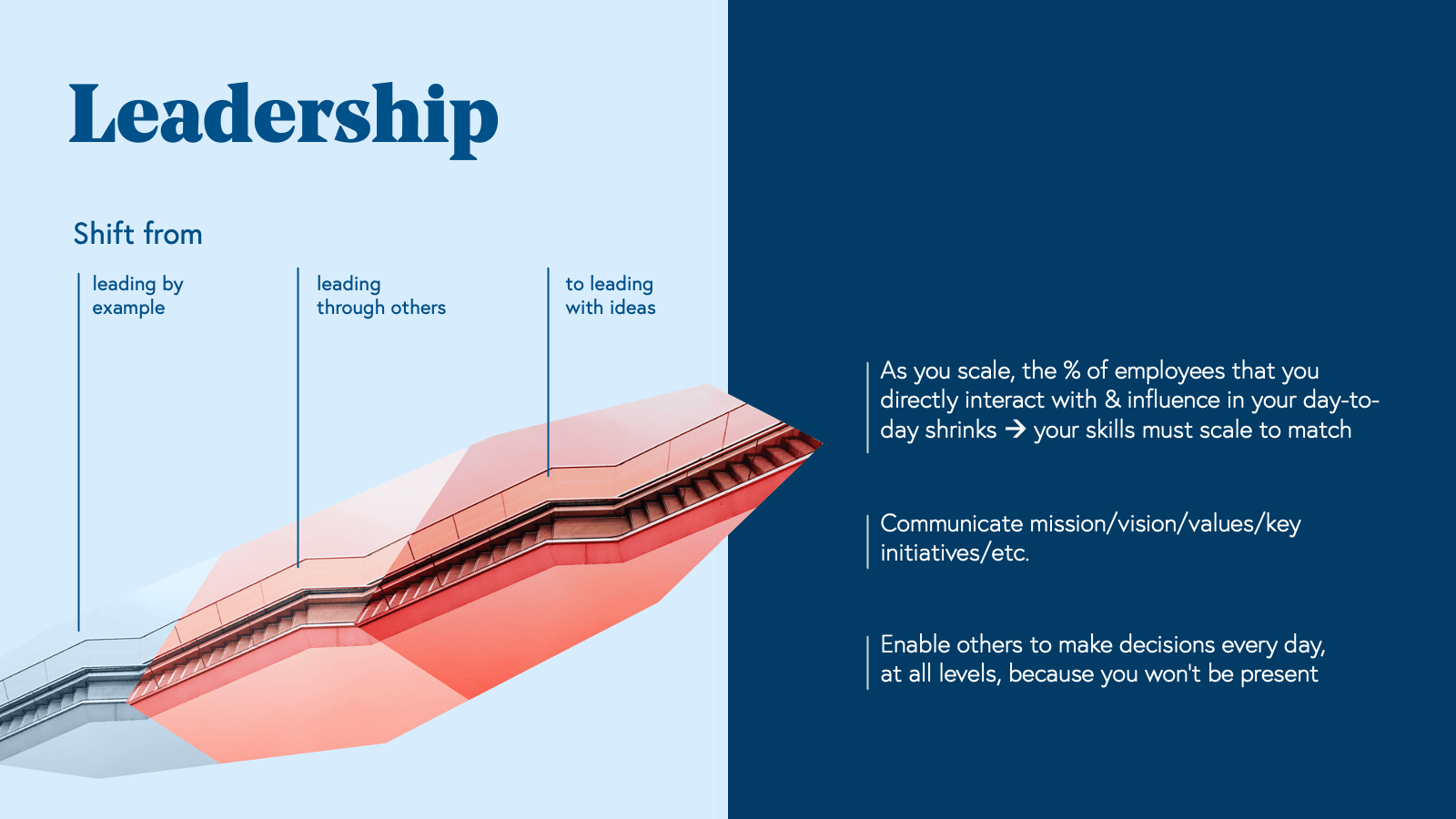

1. Lead by ideas instead of example

In the early days of a startup, as the CEO, it’s natural to lead by example. It’s likely you’ll personally interact with most of your employees on any given day, so they can observe how you think, how you problem-solve, and how you embody your company’s values. But as you grow your team, the percentage of employees you’ll personally interact with on a daily basis will shrink. This means you need a new leadership approach. At the $1-10 million stage, this usually takes the form of leading through other leaders—setting direction and trying to lead through your executives who in turn are leading their teams.

Once you reach the $10-100 million stage, your most efficient route to reach all employees is to lead through ideas. By sharing meaningful concepts via stories, you’ll allow your employees to quickly make decisions that support your vision without needing to physically be in the room.

I felt the need to shift to ideas-based leadership when I was at SendGrid. In the early days, all employees felt a great degree of ownership. Problems would get surfaced immediately—they would get yelled about, complained about, talked about over lunch. But as we grew to hundreds of employees, folks would see the same problems but wouldn’t feel empowered to voice their concerns. They might think, “Well I’m just an individual contributor, that's somebody else's / management’s job.”

At our next company kickoff in 2017, I told about 400 of our employees, known as Gridders, a story about automotive manufacturing in Japan (and implored them to bear with me, promising it would relate back to software in the end!). In the 1980s, Japanese cars were renowned worldwide for being top quality and efficiently made—therefore much more affordable. The rest of the world marveled at how that level of quality at such a low cost was possible.

Japanese automotive manufacturing became the subject of much study, and researchers learned about a powerful methodology employed by one of the carmakers, called the Toyota Production System (TPS). One of the key innovations of the TPS was that in all manufacturing plants, there was a cord called the Andon cord hanging next to all employees on the assembly line. If any employee yanked it, it literally shut the production line down. Employees were told to pull this cord when they noticed a quality issue.

As soon as an employee pulled the Andon cord, managers and workers would flock to them… and the first thing they were trained to do was to say, “Thank you.” Why? Because this person was preventing the entire assembly line from replicating a problem that would be much more expensive to fix later in QA. Then the team would work to get to the root of the problem. Empowering hourly wage workers to shut down a production line generating tens of millions of dollars a day was very contrarian in its day. But empowering workers on the floor who were closest to the problem to flag problems was Toyota’s key to success.

"Empower employees to pull the Andon cord."

The room full of Gridders got it right away. I told them, “I need you all to feel empowered to pull the Andon cord when you see something that is broken in our company. If you are brave enough to do this, every leader in this room will thank you.” This story really stuck. For years to come, Gridders would say, “I need to pull the Andon cord” when they spotted an issue—or opportunity! It's one thing to simply tell your employees what the company’s values are, but it’s entirely another to communicate an idea through a story. By giving employees a common language to name challenging issues, and a story that got lodged in their memories, I found a way to lead in rooms where it was impossible for me to be physically present.

2. Widen your aperture drastically to think long-term

At an early stage startup, a founder is likely pondering questions like, “Am I gonna make payroll next month? Are we getting new customers signed up? Are they validating our vision?” Most of these questions are very near-term and their progress will likely be measured on a weekly and monthly basis.

But as your company matures, the aperture starts widening. From $1-$10 million, you’ll probably start thinking in quarters and one fiscal year (welcome to the “Annual Board Plan”), versus weeks and months. But you're still rarely thinking about anything beyond the year ahead. But when you begin scaling from $10-100 million, it’s time to start thinking about multi-year plans. The question becomes, “How does this year's activity position us for next year's success?” If you don’t make the right investments now, there's no chance you’ll have planted the right seeds to be where you need to be in two years.

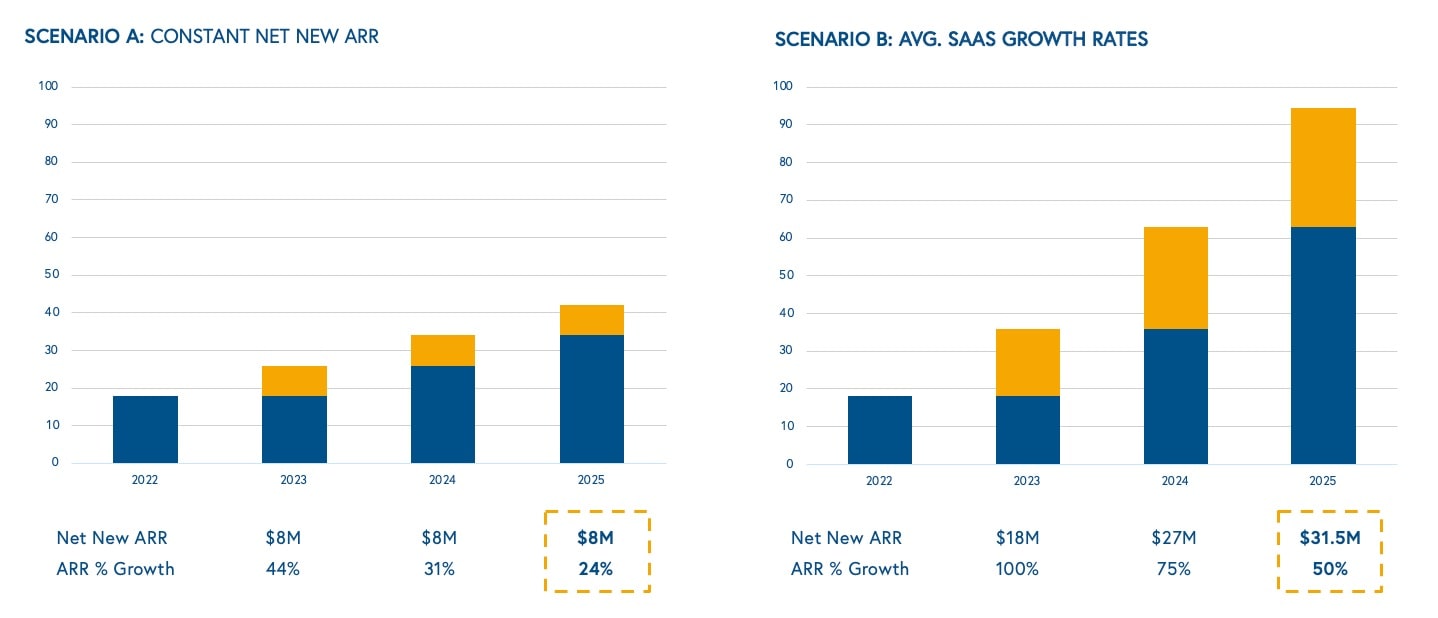

It can often be hard for employees to wrap their heads around what it means to maintain a high growth rate, at scale, in the years to come, with a narrow aperture. That is, it’s hard for them to internalize how the law of large numbers puts an inherent downward pressure on their future growth rates. At first blush, they may assume that simply continuing the hard work that they’ve already been doing and winning customers in the marketplace at roughly the same scale year after year is sufficient. But mathematically, a constant amount of growth will yield an ever-declining growth rate. It’s just math. A constant numerator (absolute dollars of a new revenue) over a growing denominator (the absolute dollars of the total business) will lead to a smaller percentage. So if employees are not thinking big, the growth rate will decelerate rapidly. At a high growth SaaS company, this would be failing at our goal to scale the business and become an IPO-worthy company. But you wouldn't see that unless you took a multi-year view of the problem.

That’s why I’d circulate a version of the graph above to help employees understand the long view. The graph on the left simply shows what would happen to a growth rate if a constant ARR amount is added each year (drops precipitously, in this example, from 44% to 24%). The graph on the right shows how much net new ARR is required to hold a high level of growth. In this example, it shows that the company would need to add ~$35 million in new ARR in year three, which is literally the size of the entire company in year zero! (In other words, this company would have to add as much revenue in year three as they did life-to-date, just to hold a reasonably high-growth rate). Helping them see a multi-year vision allowed my employees to understand that we were going to have to think bigger, and make big bets and investments now in order to generate meaningful revenue streams in the future to hold our growth rate.

Annual planning is another example of an area where you need to see the bigger picture. As an early stage startup, annual planning is typically pretty minimal. After all, the focus is more about getting through the year than planning the next one. At a later stage startup, planning for the coming year might start to feel relevant around November or December. But when you’re scaling beyond $10 million, the date moves further and further back in the year because you recognize that your investments are always impacting the next calendar year—and that these investments take time. For example, once we got to $50 million at SendGrid, our annual planning process would begin in June or July.

3. Find your communication rhythm

In my humble opinion, the hardest part about scaling a business from $10 million to $100 million is orchestrating hundreds of humans to work together, in concert, on the right set of goals. As the leader, you need to establish the right rhythm of communication for the business.

The rest of the SendGrid leadership team and I believed that the more we communicated, the more we were empowering employees to make better day-to-day decisions. It's impossible to expect your individual contributors and managers and directors to make the right calls tactically if they don't understand the strategy. But we had to find a way to do this without consuming too much time or effort. When I joined SendGrid and the company was at $30 million in ARR, we had a weekly all-hands meeting. But as we kept growing, we realized we weren't able to keep delivering high quality and impactful content that frequently. There was just too much happening. So we decided to move to a monthly cadence.

In addition to these monthly updates, we decided we were going to have two major all employee events—an annual kickoff in January and another event in the summer. In January, we laid out the major priorities and initiatives for the year and explained in detail why they mattered and how they fit into the big picture. Each initiative had clear owners, goals, and metrics associated with it. We ensured that everybody understood the relative importance of the project so that they could make trade-offs. Then in the summer, we gave progress updates on how each initiative was tracking, and made periodic reassessments of our goals and plans based on things like changing market conditions. This allowed everybody to put their heads back down and finish the year strong.

4. Expect increasing role specialization—and be prepared for personnel switch-ups if needed

Role specialization is a tough topic for many early-stage startup employees because many are drawn to the fun of getting to wear “multiple hats.” If you're in marketing at a startup, one day you'll be changing something on the website, the next day you'll be planning an event, the next day you'll be figuring out the positioning. But a more mature business demands specialization.

Once you pass $10 million in ARR, you need to shift away from having employees who are general athletes—that is, good at many things, but not excellent at one thing—towards having Olympic-level athletes at one sport. You need to narrow the swim lanes to focus on landing talent that is world class at a single discipline. This specialization often prompts many early employees to start looking for their next exciting series A startup. And there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that. As a leadership team, you should be supportive of these folks and help them find their next role so you can recruit the right person for the seat.

As you're backfilling these roles, aim to bring on talent with a proven track record at a business that’s two to three years ahead of yours. Many leaders make the mistake of hiring people for the skills that they need today. But the problem with that logic in a high-growth business is that it takes three to six months to hire the right person and then another three to six months for that person to become productive. Your company will be incredibly different in 12-24 months, so you always need to hire for who you want your company to be a year or more from now. But those hiring ambitions need to be aligned with the reality of the business. You want to hire for the future, but not too far out.

Too often scaling leaders hire for an incredibly impressive resume of an exec at a multi-billion-dollar company. It’s not a given that it won’t work out, but my experience is that they’ve just been too far away from smaller scale businesses to deal with the lack of infrastructure. At this stage, you still need a leader to roll-up their sleeves and get stuff done.

It's also extremely valuable to hire people who have succeeded at even later stage companies because they “have seen what great looks like” (as we use to say), and can use that experience to advise on how to operate to prepare for what’s coming in the future. On the other hand, it’s also very meaningful to have employees who stay with you for the whole journey. The early stage employees are typically culture carriers. They know the DNA of the company and have the deepest possible context for all past and present business decisions. You just have to make sure they’re excited to start upskilling to specialize in one area. A healthy mix, in my experience, is the best recipe.

5. Don’t let interdependencies slow down decision-making

Large companies are notorious for making decisions at a glacial place. When you’re running an operation with even hundreds of employees (let alone thousands), the sheer volume of dependencies for every decision you make is staggering. Let’s say you want to update the pricing for a product. In order to make this decision, you have to get feedback from the sales team on how they think the market will react to the change, talk to the website team to make sure they have time to adjust the pricing page, make sure the billing team can change back office systems to make sure the invoices are correct, and more. The days of quick and easy decision-making huddled around a whiteboard are over.

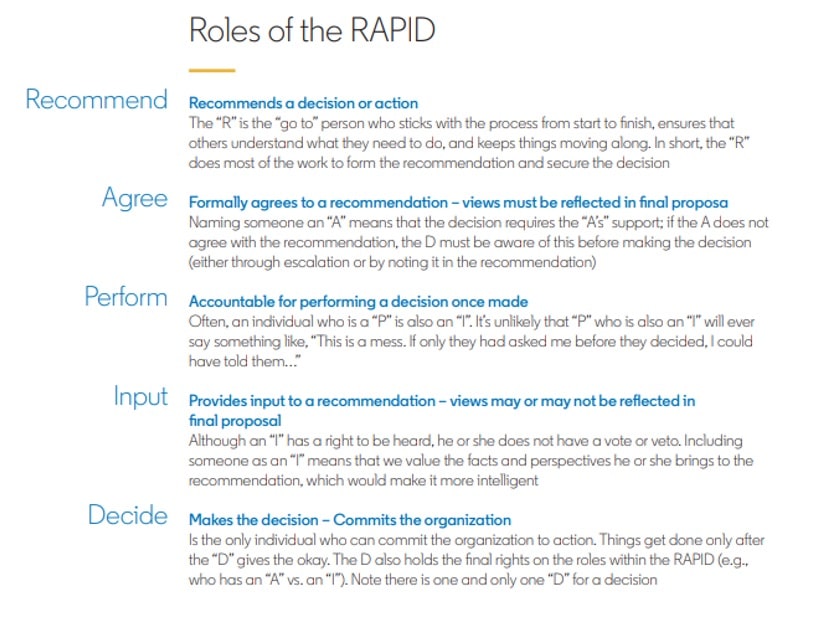

Everybody hates bureaucracy. Nobody enjoys when decision making slows. So at SendGrid, we adopted the RAPID decision-making framework from Bain & Company. You can pick any decision-making framework, including RACI, DACI, among others. It only matters that you pick one and stick to it. We told employees that if they were being held up on making a decision for more than 48 hours, then they should “call a RAPID.”

Employees were encouraged to talk to their immediate manager and identify the people that need to come together to make a decision. They’d figure out who had the decision-making authority and identify a timeline over which that decision would be made. This process really accelerated the velocity of our decision making. It gave everybody a framework to get themselves unstuck.

6. Bake culture into every stage of the employee lifecycle

When scaling a company, nearly everything changes. But one of the few things that stays the same—if you make it a conscious choice and get it right—is culture. And I’ll say this here—you cannot scale your business if you do not scale your culture. If left to chance, you can lose control of your culture very quickly. If you have 100 employees and you plan to hire 100 more by the end of the year, more than 50% of the people in every interaction will be brand new. Every time that somebody deviates from the culture without being called out, you give tacit approval to the behavior. You can imagine how quickly your culture can morph if you're not proactive in managing deviations.

At SendGrid, I would personally spend 45 minutes with every new batch of employees as we scaled from 100 people to 400 people. I would talk about why culture mattered so much to us and implore each of them to become a steward of the culture. I told them they needed to call out deviations and celebrate great examples of our values being lived. The investment of my time made it very clear to every Gridder, I believe, that this was not just talk or posters on the walls — that we were deeply invested in culture as a company.

To reinforce our culture, we built a systemic set of processes across the entire employee life cycle. For example, we included a whole section about our values on our Careers page that introduced our company values, “the four H's”: Happy, Hungry, Humble and Honest. We included a video where I talked about the kinds of people that I thought would love the SendGrid culture and people that wouldn't (because your culture has to have some edge to it—it can't be for everybody!)

In our hiring process, each interviewer was assigned one of the H's and given questions to ask to assess whether or not we thought this candidate demonstrated this quality. For example, we might give the prompt, “Tell me a little bit about a professional accomplishment of which you’re most proud.” Then we’d listen and do a pronoun count - how often did they say “we” and how often did they say “I.” If they spoke more about themselves than others, we’d give them another chance: "Wow - that’s amazing! You must have been working with a great team to accomplish all that?" If they gave credit and praise to other team members, it was a positive sign. And if they didn't, it was an indicator they weren’t likely to be a fit (might be lacking the Humble H).

As part of our quarterly all employee meetings, we had our “Four H Awards” where employees could nominate their peers and vote for the person who best exemplified our values. The awards ceremony sent a strong signal to everybody in the company about how important it was to us to celebrate culture carriers. (These awards were invariably every Gridder’s favorite part of our All Hands! It is so much fun to celebrate the teammates who make coming to work everyday a joy!) Our annual reviews also had a whole section based on culture, and exemplifying these values was a major factor in who got promoted. The investment that a leadership team needs to make to scale culture is significant, but unquestionably worthwhile to create the environment where excellent work happens. We often said, “if we can make SendGrid a place where every Gridder can come and do their best work, every day, with obstacles removed and opportunities created, there is nothing we can’t accomplish together.”

Scaling successfully is about seeing the longview

Scaling a high-growth company is not for the faint of heart. If you don't get ahead of the changes that start coming at you hard and fast, it'll be chaos at your company. One of two things may happen—either it'll be dysfunctional because you haven't orchestrated all the humans in the right way or it’ll show up in the financials. (And if you hit a growth wall, you might be in the penalty box for two years while you build your way out of it, since business initiatives have such long lead times.) With some thoughtful planning—and a willingness to evolve each year as your business scales—together, your team can successfully navigate those awkward “teenage years” of a company’s life. It’s all part of development! This change will lead to growth before a company is ready to take on the complexities of a public company life.