Ten lessons from a decade of vertical software investing

Insights on how vertical software founders can choose their markets wisely, maintain enduring growth, and build industry-defining companies.

A few years ago, we published the initial version of our vertical SaaS manifesto. Since then, we have seen vertical SaaS continue to evolve—especially as new forms of monetization arise and augment the traditional software-based model. Accordingly, we have updated this piece to reflect the changing face of vertical SaaS, deeper insights into pricing and packaging, and the emerging importance of B2B payments in vertical SaaS in a new Bonus Law. At Bessemer, we are more confident than ever about the continued proliferation of software in every industry and we look forward to backing the next great vertical software founders doing so.

What we came to learn through investments like Shopify, Procore, Toast, ServiceTitan, Mindbody, nCino, Disco, and many others, is that vertical software companies could grow to be much larger than we expected. By focusing on a vertical market, these companies are able to trade market size for market share and in some cases achieve 50%+ market penetration. In vertical markets, one or two vendors often dominate and capture most of the value. Today, every industry runs on software, making the vertical software opportunity more valuable than ever before.

Executive summary: Ten lessons from a decade of vertical software investing

|

Lesson |

Key takeaway |

|

1. Market leadership |

Focus on dominating a vertical via unmet needs, overlooked segments, or disruptive tech. |

|

2. Layer cake growth |

Continuously add and cross-sell new products/services. Start before growth slows. |

|

3. Integrate services |

Enable continuous monetization via payment processing, payroll, or lending. |

|

4. Monetize end users |

Launch marketplaces, facilitate consumer lending, or build direct-to-consumer arms. |

|

5. Data as an advantage |

Build data networks, benchmarking, machine-learning enhancements, and subscription data services. |

|

6. Dynamic pricing |

Frequently experiment with pricing/packaging instead of relying on defaults. |

|

7. Upmarket expansion |

Move from SMBs to enterprise as necessary, with focused product and team changes. |

|

8. Cautious M&A |

Only pursue acquisitions with clear ROI, and prioritize post-merger integration for product, customers, and teams. |

|

9. Build moats |

Use scale, switching costs, and platform/network effects to defend dominance. |

|

10. Exit optionality |

Prepare for IPO, acquisition, or PE exit based on business metrics and market realities. |

|

Bonus: B2B payments |

Vertical SaaS has major emerging opportunities in B2B payments and spend management. |

With the benefit of watching from the sidelines, we’ve tried to capture a decade of lessons on how to build industry-defining vertical software companies.

Lesson 1: The goal of every vertical software company should be to find a path to market leadership.

For an aspiring vertical software business, market leadership is the prize. Over the past decade, we’ve seen three successful paths to market leadership:

1. Attack an underserved market: Historically, the most valuable vertical software businesses have been built by serving industries that have lacked access to software. Simply put, it’s much easier to capture leadership in a greenfield market without incumbents.

In this spirit, Procore‘s* founder, Tooey Courtemanche, realized that the construction industry was woefully underserved by existing software products. He took advantage of mobile Internet access on the job site to build a modern way for the construction industry to collaborate in the cloud. Procore has grown to lead the industry with an end-to-end construction management platform, creating a multi-billion company in the process.

"Attacking an underserved market” can take different shapes in the trajectory of a startup:

- Underserved industry: Like Procore, ServiceTitan* attacked an entire field services industry underserved by modern software. Now a multi-billion dollar company, ServiceTitan provides a full management tool for owners who are fed up with running their plumbing or HVAC business on pen and paper.

- Underaddressed market segment: In markets with strong enterprise incumbents, we’ve seen startups win by catering to a neglected market segment. Companies like Mindbody**,* Clio*, and Weave* found their path to market leadership by starting in the SMB segments overlooked by incumbents.

- New and growing industry: New verticals lack strong incumbents, opening the door for startups to capture market leadership. Shopify* rode the wave of long tail e-commerce, Dutchie is attacking the emerging cannabis market, Aurora Solar is benefiting from growth in the solar installation market, and Mambu has built a multi-billion dollar business by catering to a new generation of fintechs and digital banks.

2. Address an overlooked problem: Once an industry has been served by a vertical market leader, they can be very difficult to unseat. In more mature markets, we’ve seen new leaders emerge by attacking problems that are poorly addressed by market-leading incumbents.

For example, nCino* found an opportunity to digitize the processing of commercial loans inside of banks. Banks had plenty of software vendors (including massive incumbents like FIS and Ellie Mae) but no one was paying attention to the commercial loan origination process.

Look under the hood of a company in any industry and you’ll find dozens of business processes that have yet to be productized or poorly served. These are ripe for a best-of-breed market-leading vertical solution.

To get a taste for what underserved problems look like in a specific vertical, check out Mike Droesch's supply chain roadmap.

3. Unseat sleepy incumbents: Existing market leaders have big advantages making it extremely difficult to unseat incumbents. In the auto industry, three 40+ year old software companies—CDK, R&R, and Cox—have chased away dozens of new entrants over the years and grown to over $100 billion in value.

However, time and time again, we’ve seen exceptional founders leverage a platform shift to unseat incumbents. This is often driven by a technology catalyst that gives new entrants an unfair advantage.

*We saw our portfolio company Toast pull this off in the restaurant point of sale (POS) market. Many thought this market would be forever dominated by NCR and Oracle. But Toast’s founders had three radical insights:**

- They could leverage Android hardware to build a better tablet-based experience for restaurant workers than the PC-based status quo;

- They could use cloud delivery to constantly make their software better than the legacy on-premise incumbents;

- By integrating payment processing and capturing payments revenue, they could sell their software at a much lower price point than incumbents and competitors.

With a vastly superior tablet-based product at a disruptive price point, Toast was able to take massive share from NCR/Oracle in less than a decade and build a $500+ million revenue business.

Unseating incumbents is difficult but with a product that is better or cheaper, new entrants can overcome the switching costs that give vertical incumbents their advantage. However, this is the toughest path to market leadership because it requires your new solution to be wildly cheaper or better (or both).

Examples include:

Developer platforms: In 2013, Bessemer published the eight laws of developer platforms, a set of best practices for developer-oriented software companies, an emerging category at the time. In category’s growth has since exceeded our wildest expectations.

With every industry hiring developers and digitizing their business, we’re seeing the emergence of vertically-focused developer platforms.

In financial services, APIs like Plaid, Stripe, Adyen, Marqeta, Alloy**, and [Lithic](https://lithic.com/) facilitate payments, data sharing, and other payments-specific capabilities.

In retail, “headless” e-commerce platforms and API-driven tools like Shippo* are giving developers more control over the retail experience.

We’re starting to see developer platforms emerge in other verticals like healthcare, travel, education, and telecom.

Looking ahead, we expect to see the rise of vertically-focused developer platforms as even the most traditional industries increase their investment in software and IT. For further reading on developer platforms, read Ethan Kurzweil’s newest laws on this unique type of software model.

Lesson 1 key questions and answers

Q: What are the main ways vertical software companies achieve market leadership?

A: Companies can attack underserved markets, address overlooked problems, or unseat sleepy incumbents using technological advancements. For example, Procore succeeded by serving the under-digitalized construction industry, while Mindbody gained leadership by targeting overlooked SMBs.

Q: Why is market leadership so important in vertical software?

A: One or two vendors often dominate vertical markets, capturing most of the value. There's little value in being a distant third.

Lesson 2: The best vertical software companies build a layer cake of new products that drive continuous growth.

There is one thing that separates the good from the truly great in vertical software—a “layer cake” strategy of building additional products to sell into their core vertical market.

To put this in perspective, look at Veeva, the leader in software for the life sciences industry. Veeva got its start by selling CRM software for pharma sales reps. Before the company hit market saturation in the CRM market, Veeva’s founder started to work on the company’s next act. In 2012, Veeva launched Veeva Vault, a new product line serving not only the sales function but also the research and clinical operations functions.

While Veeva’s CRM product continues to grow at an impressive 10-15% annual growth rate, Vault has driven the majority of the company's recent growth. Year after year, Vault has steadily expanded in breadth with dozens of products. Thanks to this layer cake strategy, the company has sustained a revenue growth rate of about 30% over nearly a decade.

Today, Veeva is approaching $2 billion in revenue and showing no signs of slowing.

The key lesson from the Veeva experience is that vertical software CEOs need to start thinking about their “next act” years before their core product starts to slow. It can take two to three years to launch a new product and grow it to a meaningful scale.

When it comes to building new products to cross-sell into an existing customer base, we’ve seen a few tactics used successfully:

- Ask your customers. Leverage customer advisory boards, on-site visits, surveys, and feedback from your sales team. Don’t just ask for product ideas but try to understand your customer’s business problems and design software to solve them.

- Follow the P&L. Look at your customer’s P&L from top to bottom to identify the biggest drivers of revenue and cost. Develop products that drive revenue or reduce expenses for your customers.

- Draw inspiration from the competition. Analyze what other software your customers are buying. Attack the most vulnerable competitors with a better, cheaper, and/or fully integrated alternative.

- Study other verticals. As you design your layer cake, draw inspiration from what market leaders in other verticals have been able to cross-sell—especially the integrated services we’ll discuss later.

In the early days, it can be tempting to work on many products concurrently, but focus is key. The most important lesson we’ve learned from watching portfolio companies on this journey is that it requires ruthless prioritization. As a resource-constrained startup, limit yourself to one “next act” at a time until you’ve built a mature multi-product muscle.

However, once you get to $100+ million of ARR, you no longer have the luxury of being hyper-focused. You’re now dealing with the complexity of a multi-product company selling into multiple market segments.

Instead of trying to manage by committee, Veeva has a product owner and GTM owner for each of its products and market segments. These "two in a box" owners are focused full-time on their piece of the layer cake. Their financial incentives are tied to the success of the new product, and they are given an independent team to move quickly and execute without dependencies elsewhere in the company. Typically, their compensation is tied to the success of this new product and they are made to feel like true owners(Working Backwards does a nice job of explaining how Amazon does this). Having a clear owner (and arming them with resources to be autonomous) is the best way to manage multi-product complexity at scale.

Lesson 2 key questions and answers

Q: What is the “layer cake” strategy?

A: It involves continuously developing and launching new products to cross-sell into your existing customer base, ideally before core product growth slows down. Veeva, for instance, expanded beyond CRM into multiple life sciences operational tools.

Q: How should new product ideas be identified?

A: By asking customers, analyzing competitors, studying other successful verticals, and following customer P&Ls to spot valuable pain points.

Lesson 3: Some of the best layer cake opportunities are integrated services. Easy to cross-sell and feel "free" to your customers.

Market-leading vertical software companies have the luxury of adding “integrated services” like payment processing to their layer cake. Most financial services like payment processing, payroll, and lending are commodities. As the trusted software vendor to your vertical, you have the right to win against generic third-party providers by delivering a vertical-specific offering that is often more usable, more affordable, and better integrated with your software.

The beauty of this approach is that you’re not asking customers to reach into their pockets and buy more software. Instead, you’re replacing something that customers are already paying for which makes the cross-sell feel “free” and lowers sales friction.

Over the past few years, we have seen an explosion in these kinds of integrated services including:

- Consumer Payment Processing: By far the most common and valuable integrated service is consumer payment processing. Many of the vertical software companies in the Bessemer portfolio including Shopify, Mindbody, Toast, ServiceTitan, Clio, and Brightwheel. These companies earn up to half their revenue from delivering integrated payment processing solutions to their merchants and keeping a cut of the interchange revenue.

-

Payroll: Like payment processing, payroll is a commodity service dominated by generic providers. Vertical software companies are in a unique position to build fully integrated payroll processing solutions like Restaurant365* and Toast are doing in the restaurant vertical. An integrated payroll offering can deliver industry-specific features, reduce the need for accounting reconciliation, and provide better service than generic legacy providers, like ADP or Paychex.

The dollars in payroll are massive—representing $10-$25 per employee per month depending on the industry and depth of functionality. And the opportunity has become much more actionable in recent years thanks to a new ecosystem of third-party providers that make it easier to deliver integrated payroll, such as Gusto, CheckHQ, and Zeal.

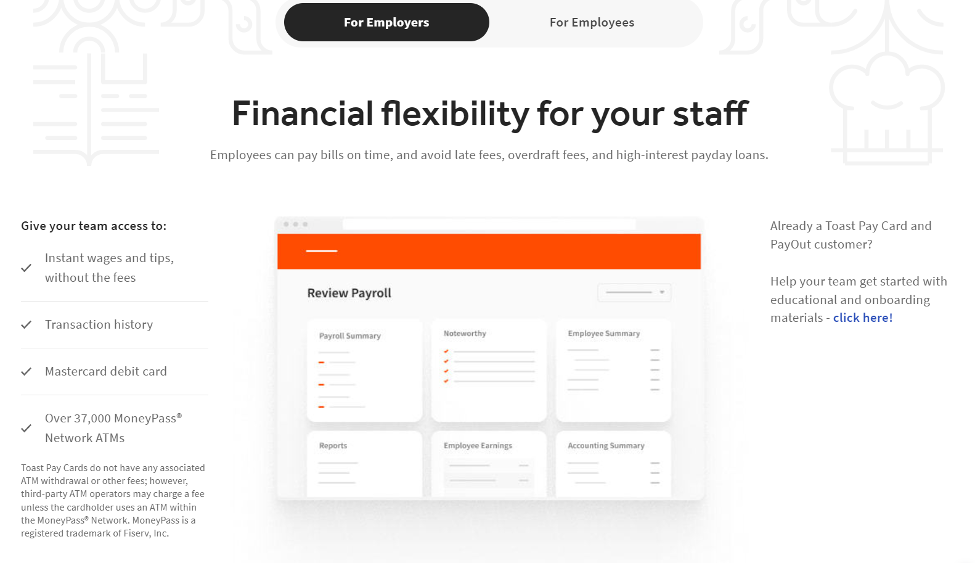

Vertical software companies can further leverage card issuing to pay employees via debit card rather than check or direct deposit. Through this, employees access wages faster, employers benefit from happier employees, and the software company issuing the payroll cards captures interchange revenue in the process. Toast, for example, is launching the Toast Pay Card, which provides employees with instant access to wages and tips once a shift is finished. The Toast Pay Card has a variety of benefits including providing instant and early wage access, reducing operational overhead of paper checks, and eliminating the requirement of a bank account for the employee, which is important in an industry where many are unbanked.

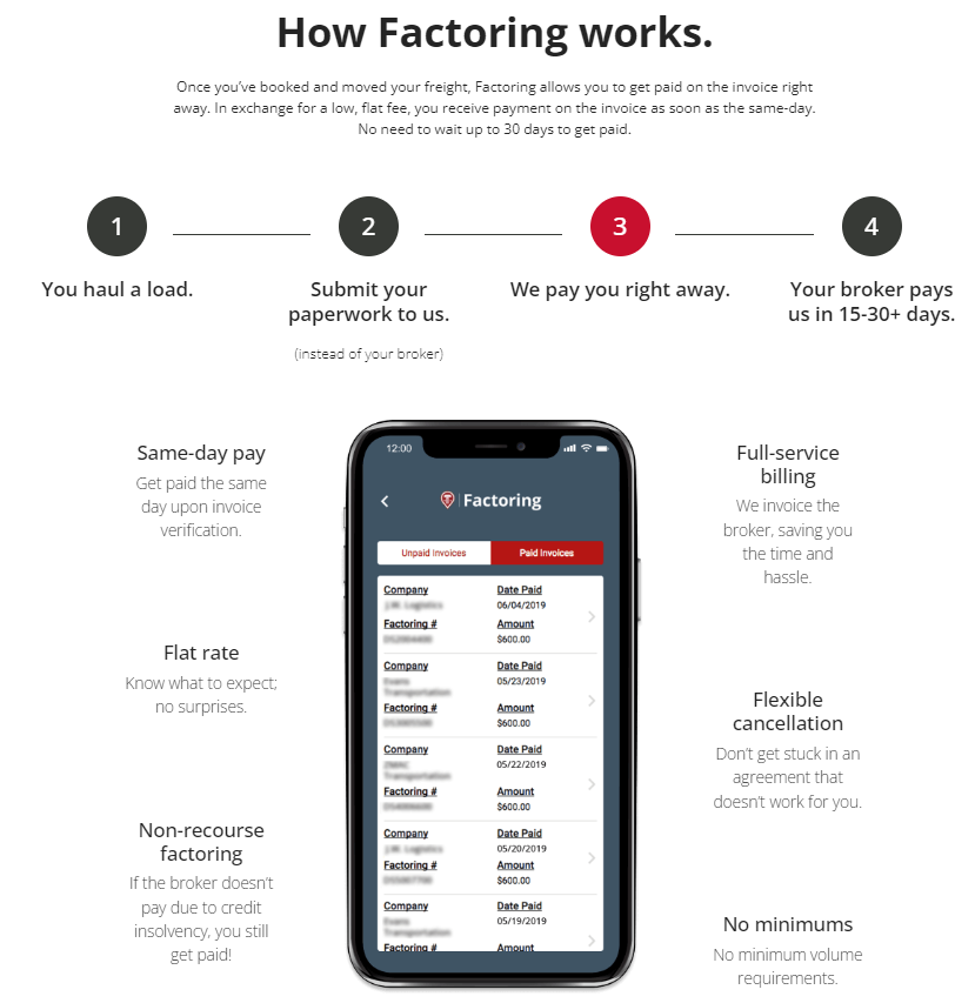

- Lending: Software companies like Shopify are starting to source and underwrite business loans. Vertical software providers that have visibility into cash flows are particularly well-positioned to originate and underwrite loans. For example, Procore* is delivering loans to help construction companies finance the purchase of construction materials at the moment when a new job is awarded to them. Truckstop is providing loans to trucking companies after they’ve completed a job secured by the payment that is owed to them. Mindbody is offering a cash advance against future payments processed through the Mindbody platform.

- Communication: No one loves their phone company. Vertical software businesses can replace commodity third-party phone service with an integrated VOIP/SMS offering. Weave, for example, has had success in the dental, veterinary, and medical verticals by bundling VOIP and SMS services with software tools to provide an end-to-end customer communication platform.

- Managed Services: Managed services are a dirty word in the software business. They are typically low margin, hard to scale, and deliver low-value non-recurring revenue. But there is a rare breed of high-margin, recurring, and scalable tech-enabled services that can be an attractive addition to a software business. Athenahealth and DocuTap* rode the wave of increasing complexity in medical billing by delivering a lucrative managed billing and collections service.

As vertical software companies explore ways to leverage their role as the “operating system” for their businesses, we see them branching out into other lucrative integrated services, which we dive into as the first prediction in State of the Cloud 2022.

Lesson 3 key questions and answers

Q: What types of integrated services can vertical software companies offer?

A: Examples include payment processing, payroll, lending, communication tools (like VOIP/SMS), and managed services tailored to their industry, often feeling “free” to customers by replacing existing expenses.

Q: Why are integrated services so lucrative?

A: They can represent a large share of revenue and have low sales friction since customers are already used to paying for them elsewhere.

Lesson 4: For consumer-facing software, there's a unique opportunity to monetize the end customer.

Most vertical software companies built their businesses by solving problems for internal business users, often overlooking consumer end-users in the process.

With many internal problems solved by a prior generation of software, we are seeing newer success stories in vertical software focus on consumer experience and “systems of engagement” to unlock new opportunities.

Take Brightwheel, a provider of software to the childcare market. Brightwheel’s founder Dave Vasen realized that parents want to see what their kids are doing and communicate with their childcare providers. By focusing on the needs of the childcare consumer, Brightwheel created a new category for childcare software that did not exist before and is now bigger than most of the incumbents.

Similarly, Blend built a multi-billion dollar public company by arming banks with software to process online mortgage applications. The industry was full of incumbent software providers but all were focused on internal use cases. Blend was the first to approach banking software from the perspective of the bank’s customer.

The vertical software business that also interfaces with end-consumers can monetize those consumers in creative ways:

The vertical software business that also interfaces with end-consumers can monetize those consumers in creative ways:

- Consumer marketplaces: Mindbody sells software to gyms and yoga studios to help them run their business. With over 50% market share, Mindbody built enough supply-side inventory to launch a consumer-facing marketplace for booking classes (much like OpenTable has done in the restaurant industry). Mindbody is able to monetize each booking and enhance the value of its software.

-

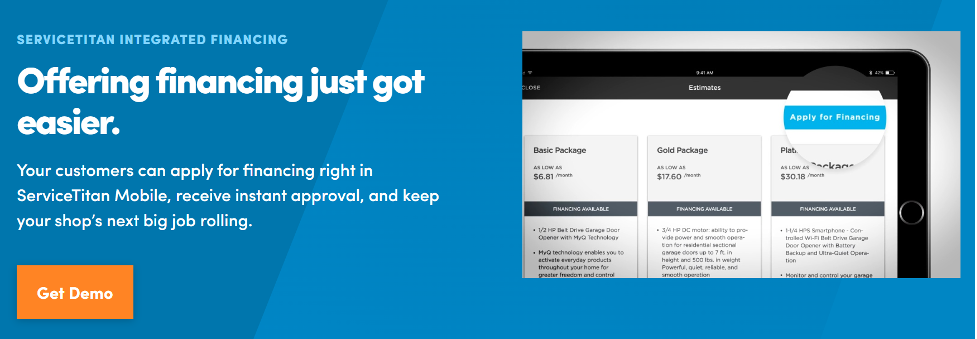

Consumer lending: ServiceTitan has partnered with a lender to make it easy for its home services companies to provide financing for their end-consumers when they are making a big purchase. ServiceTitan helps its customers close more sales by providing the consumers with instant financing. And ServiceTitan earns a meaningful commission for facilitating the transaction.

- Booking fees: Some B2B2C vertical software companies are finding ways to monetize the consumer instead of the merchant. FareHarbor is a provider of software to the activity and tour operator market. While most of its competitors charged operators a subscription fee, FareHarbor gave away their software for free and instead earned revenue by charging the end-consumer a transaction fee. This disruptive pricing model gave FareHarbor an advantage over more expensive competitors. We’re frankly surprised that we don’t see more verticals take this approach of “give the software away for free and monetize the consumer.”

- Consumer products: Blend powers the online mortgage application portals for banks. Because it knows when a consumer is applying for a mortgage, it is in a unique position to cross-sell other products consumers need as part of the mortgage process. To capitalize on this opportunity, Blend delivered a fully integrated title insurance experience for consumers as part of its mortgage application process.

Lesson 4 key questions and answers

Q: How can vertical software monetize end users directly?

A: Through consumer marketplaces, consumer lending solutions, booking fees, and cross-selling consumer-facing products, as demonstrated by companies like Mindbody and Blend.

Q: Why is this often overlooked?

A: Most vertical SaaS companies focus on internal business users and miss opportunities to deliver and monetize consumer-facing features.

Lesson 5: Data remains one of the most under-exploited opportunities in vertical software.

Many of the most valuable vertical technology companies like FICO, Esri, Verisk, CoreLogic, Refinitiv, and IMS are data businesses at their core. They have grown to billions in revenue by selling data to vertical markets and have many of the qualities that make software businesses so attractive (high margins, recurring revenue, barriers to entry, operating leverage, etc.)

To date, few application software companies have built data businesses. But we think this is one of the under-served opportunities to grow revenue and build deeper moats.

Value creation can occur in a few different ways:

- Building data plumbing: Among the most valuable vertical software businesses are data networks which facilitate the flow of information between industry stakeholders. In the insurance world, Vertafore and Applied Systems have built vertical leaders by integrating with insurance carriers to provide agents with access to pricing and quotes. These data networks enhance Vertafore and Applied’s dominance. To compete, a new entrant would need to build and maintain 100+ carrier integrations.

- Benchmarking data to drive user insights: Cloud deployment gives vertical software companies visibility into data across their entire user base. Guidewire, a publicly-traded provider of software to insurance companies, harnessed the power of benchmarking. Users can see anonymized operational metrics benchmarked across similar Guidewire customers. Benchmarking is difficult to execute but remains one of the biggest under-served opportunities in vertical software.

- Leveraging data: Vertical software companies can use data to improve the quality of their product. As an example, Disco uses computer vision and machine learning to extract data from corpuses of legal documents. As Disco collects more data, its e-discovery products become more powerful. Other companies like Procore are using data to power embedded financial services products like loans and insurance.

- Selling data: As discussed, many of the most valuable vertical technology companies sell proprietary data sets. If your software enables you to capture data that is unique and valuable, consider monetizing it as a subscription data service. As an example, VTS* is taking advantage of its commercial real estate software footprint to gather and sell real estate market data about activity in the real estate industry.

These plays (data plumbing, benchmarking, machine learning, and selling data) were tough to pull off in the on-premise software world. Data lived in the customer’s server. Now data resides in the cloud and is accessible to software vendors in a way that was never possible before.

Lesson 5 key questions and answers

Q: What are the major ways to leverage data in vertical software?

A: Building industry data networks, offering benchmarking/insights, utilizing data to enhance product features (e.g., AI/ML), and selling unique data sets as new services.

Q: Why has data historically been underexploited?

A: In the on-premise world, customer data was siloed. The shift to cloud delivery now enables value-added data products and services.

Lesson 6: Pricing and packaging are the biggest missed opportunities in vertical software.

Pricing and packaging are hard. Most software companies default to gut decisions and rarely make changes. It is a missed opportunity. Pricing efforts are free ways to drive revenue growth, requiring no incremental R&D or GTM investment. In vertical markets, where logos are sparse, getting the most value out of each customer is critical.

We’ve found that many of our portfolio companies go years without revisiting pricing. Below are good signals that it’s time to run new pricing experiments:

- You haven’t made any changes in a year.

- You are rolling out new features.

- Your prospects are not pushing back on pricing.

- Other products your customers are using are priced much higher than your product.

Even when companies realize it is time to revisit pricing, oftentimes they become paralyzed by the complexity of pricing. Most pricing questions don’t have simple answers. What is the right pricing model (e.g. usage-based, seat-based, two-part tarrif, etc.)? What is the right price point for each customer persona? What are the right contract terms? How do I implement pricing changes?

If there is one piece of pricing advice we can impart it is this—pricing is never done. As your product and company matures and evolves, so too should your pricing model. However, pricing is challenging and in the face of such complexity, it is easy to kick the can down the road. Instead, try the following:

- Build a small “tiger team” with stakeholders from product, marketing, sales, and finance.

- Have a dedicated pricing point person responsible for driving the agenda and monitoring performance.

- Run regular experiments on a monthly or quarterly cadence.

- Start with simple experiments and get more complex as you build confidence and credibility.

Simple experiments can include:

- Increase pricing for a subset of new customers by 10-100% and see what happens.

- Add an automatic annual price increase to your contracts.

- Introduce a new pricing tier.

- Make an add-on module opt-out rather than opt-in.

- Charge more for professional services/implementation to increase gross margin.

- Add a volumetric or consumption-based component to your pricing.

- Adopt a tiered pricing model (good/better/best) and use “price anchoring” in your highest tier to maximize revenue from your middle tier.

- Introduce pricing increases in the context of new feature releases to give customers the feeling that they are getting value in return.

- Glean pricing insights using a Van Westenddrop Price Sensitivity analysis (see this article by OpenView on how to best leverage this model and its relative pros and cons).

- Add a self-service tier to reduce initial friction to adopt.

There are plenty of valuable resources that will inspire countless pricing and packaging experiments. We would recommend starting with the following:

- Bessemer’s Startup Pricing Journey

- ProfitWell’s Anatomy of SaaS Pricing Strategy

- OpenView’s SaaS Pricing Resources Guide

Lesson 6 key questions and answers

Q: Why is pricing and packaging described as a “missed opportunity”?

A: Many vertical software companies don’t experiment with pricing, leaving potential revenue on the table. Ongoing pricing experiments can generate growth without additional R&D/sales spending.

Q: When should pricing be revisited?

A: At least annually, when launching new features, if prospects don’t push back, or if comparable products are priced higher. Use small, contained experiments to find optimal models.

Lesson 7: Many verticals require a move up-market to sustain growth.

Vertical software companies often get their start focused on the SMB or mid-market—selling four or five-figure deals. In some verticals, there are enough customers to build a massive business in this market segment, especially if you can deliver a great layer cake (Shopify or Toast are good examples). However, in many verticals, there are too few logos to build a big SMB/mid-market vertical software business. The only way to sustain high rates of growth is to move upmarket.

The commercial lending software company nCino began by catering to the small banks and credit unions willing to work with a startup. These were initially five-figure deals. As the product matured and nCino built a reputation in the industry, the company began to move up-market with six-figure deals to larger banks. Today, nCino has over 20 customers paying over $1 million per year, including some of the largest national banks in America.

In nCino’s case, there were only about five thousand banks in the US. Without six-figure deals, our portfolio company would have never achieved IPO scale.

The march up-market can also be dangerous—hijacking a company’s product roadmap, distracting the team, and exposing the company to new risks. Adam Fisher recently discussed best practices to make the ascent upmarket.

As Adam explains, there are a few winning strategies we’ve observed over the years:

- Follow the fastest-growing customers

- Let product lead the way (not sales)

- Don’t fork the product (ever) or GTM engine (initially)

- Don’t forfeit the low end

If you start on the march up-market, you will need to be thoughtful about adapting for the enterprise. You’ll need to mature the product, harness an enterprise sales motion, reposition your marketing efforts, and build an implementation/success team to drive customer adoption. It can be hard to learn enterprise on the job and your best bet will be to hire team members with enterprise experience.

Lesson 7 key questions and answers

Q: When should a vertical SaaS company consider moving up-market?

A: When growth opportunities in the SMB/mid-market segment become limited, companies may need to sell to larger customers for sustained growth, as nCino did in banking.

Q: What are the risks and best practices?

A: Moving up-market can distract teams and complicate roadmaps. Best practices include following fast-growing customers, leading with product (not sales), and not prematurely splitting product/GTMs.

Lesson 8: Vertical software lends itself well to M&A, but should be used cautiously.

Acquisitions can be used to accelerate the vertical software layer cake. Given your vertical focus, you are in a good position to buy a product and cross-sell to your customer base. M&A can also help you consolidate the market and get to the coveted market leadership position. For these reasons, vertical software companies tend to be more acquisitive than horizontal players.

However, the majority of acquisitions are value-destructive and M&A should be used cautiously. The best acquisitions have a very clear and immediate financial ROI. The worst are often rationalized using strategic value and optimistic future growth assumptions.

Most successful software acquisitions fall into one of two buckets:

- Acquiring a new product to cross-sell: As you design your layer cake, it can be more attractive to buy rather than build. RealPage, a $6 billion real estate software business, has been wildly successful at acquiring products and cross-selling these products to its large customer base. To assess ROI, make sure that the revenue from the acquisition multiplied by your expected exit multiple exceeds the acquisition price by a healthy margin.

- Consolidating market share: In some markets, you have fierce competitors fighting for every deal. Both companies suffer from higher sales costs, higher churn, and lower win rates. If competitors can join forces, as we saw at VTS, it can be a value-maximizing event for all shareholders. Freed from bruising competition, VTS has been able to improve its financial performance, raise capital at attractive terms, and refocus its energy on product innovation. To assess ROI, make sure that the value of your stake in the combined business exceeds the value of your stake in the standalone company.

Even when the ROI is strong, acquisitions can destroy value due to weak post-merger integration. Any acquisition needs to have a thoughtful post-close game plan across three areas:

- Product: Acquisitions struggle when the acquired product is poorly integrated. Before closing the deal, figure out what you will do with the product from a technology and product roadmap perspective.

- Customers: Acquisitions fail when they disappoint customers. This is especially true in a market consolidation play where you are migrating customers over to your software. Before closing the deal, figure out how you will deliver the news to customers, how you will mitigate churn, and how you will handle the customer migration.

- People: Executives often get excited about a deal but the people who are doing the day-to-day work may not be fully committed. Before closing the deal, you need to figure out the roles and get buy-in from both your team and the target’s teams. Do not count on the founder of the company you're acquiring to stick around—they rarely do.

Find a trusted leader who will be accountable for building the plan and then owning the post-merger execution. Because the failure rate in M&A is high, make sure to start small. In our experience, the smaller deals tend to be the most likely to succeed.

Lesson 8 key questions and answers

Q: How should vertical SaaS companies approach acquisitions?

A: Focus on acquisitions with clear, immediate ROI that align with the “layer cake” strategy or consolidate market share.

Q: What are common pitfalls?

A: Value destruction can result from poor post-merger integration around product, customers, or people. Start with small deals and plan integration thoroughly before closing.

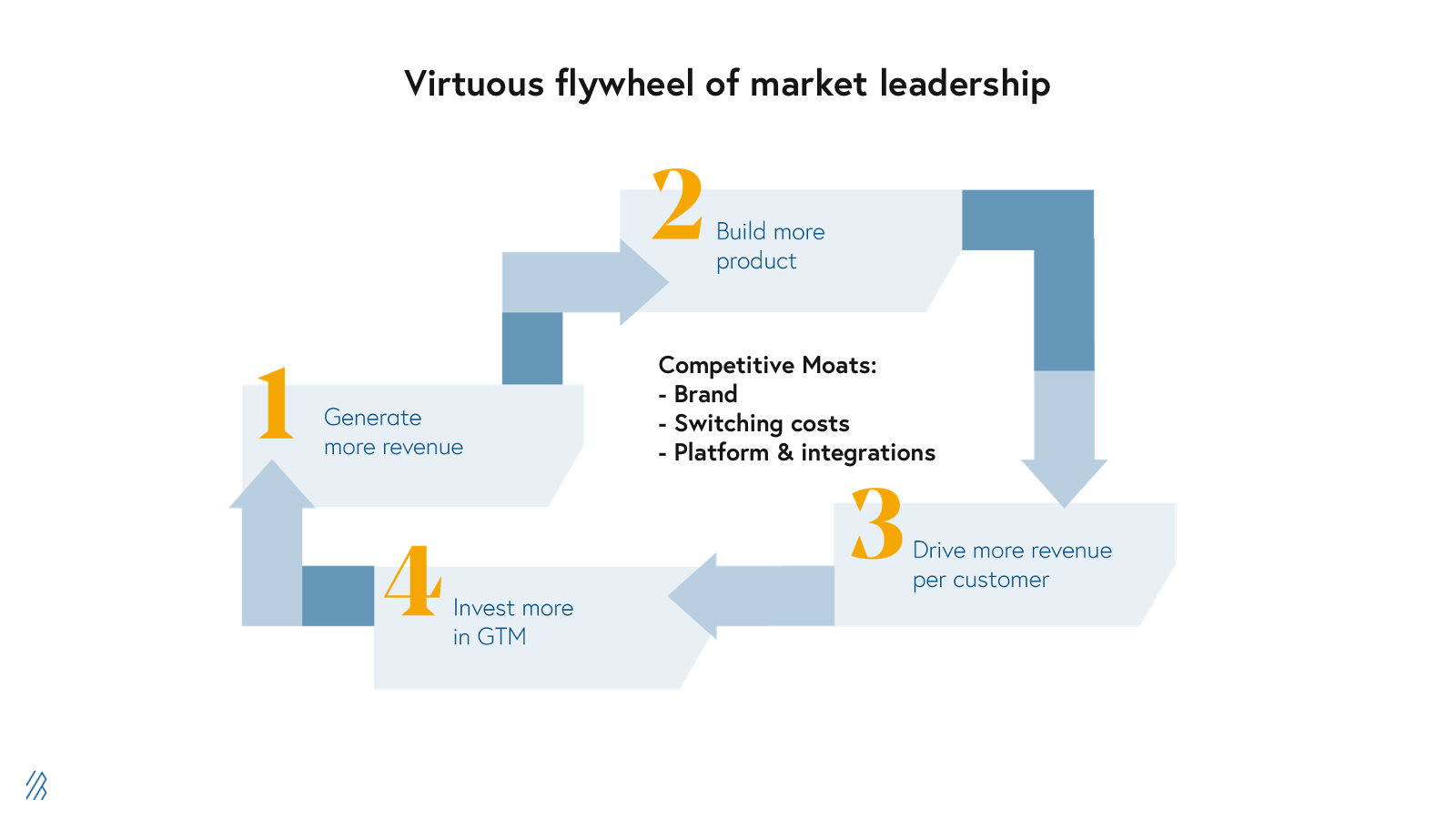

Lesson 9: Once market leadership is established, enduring vertical software companies focus on deepening competitive moats.

If you ever find yourself in the fortunate position of being a market leader, don’t wait for the next generation to take your throne. Over the years, we’ve watched vertical software companies use the following strategies to fortify their competitive positions:

1. Take advantage of scale—As a market leader, you have more revenue than the competition, enabling you to invest more in product and GTM than your competitors. This is a virtuous feedback loop. Use the revenue to build your layer cake and become the one-stop-shop for customers. Outmaneuver or commoditize adjacent point solutions before they can become real threats. Use your large GTM engine to outsell and out-market your competition. Amplify your brand to win over risk-averse customers who want to buy from the market leader, rather than an upstart.

2. Increase your switching costs—Your deepest competitive moat may be making it painful for your customers to switch (even if new entrants have better products or lower prices). We’ve seen a few smart approaches to driving higher switching costs:

- Capture customer data. Migrating data is painful and the stakes are high if the migration fails. Once an insurance agency has all their customer data in Vlocity, they’re reluctant to switch CRMs.

- Encourage third-party integrations. If your customers have gone through the trouble of integrating your software with their ERP system, it becomes much more difficult to make a switch. Across our vertical software portfolio, companies like Procore with robust third-party integrations have much higher retention than those without.

- Extend across multiple departments. Instead of a single team making the switching decision, they now need to get buy-in from multiple departments. This is how healthcare software companies like Epic and Cerner stay so deeply entrenched in a hospital despite their shortcomings.

3. Build a platform—Vertical software companies can enable their customers to collaborate with other companies in their industry. This may be the deepest moat in software-- by becoming the platform upon which the entire industry does its work, you can unlock powerful network effects.

The platform play often encompasses a few different strategies:

- Integration/API platform: Integrations and a developer-friendly API that makes it easy for customers to connect all their other software and pipe data into the platform. Samsara has quickly grown to $500M+ ARR thanks to its many out-of-the-box hardware and software integrations.

- Application platform: An ecosystem for third-party application developers that can build tools and products that exist on top of the platform. Shopify has built a $100 billion+ platform by enabling a robust “app store” of third-party applications and shipping/fulfillment providers.

- Collaboration platform: Multi-player functionality built into the platform that makes it easy for lots of stakeholders to collaborate. Canva* has built a $40 billion+ business by making it easy for creative professionals to collaborate on design projects

This is the path that Procore is taking in the construction industry. Procore is making it possible for all the key stakeholders in a construction project to collaborate. It is delivering an open API with pre-built third-party integrations. And it is making it easy for developers to build applications on top of Procore. The company’s long-term vision is for the entire construction process to be run on Procore. Its prize is to be the dominant platform for the $10 trillion-dollar global construction industry.

In the early innings of your company’s life, it’s all about growth and customer acquisition. But once you’ve reached a market leadership position, draw inspiration from vertical leaders and work to deepen your competitive moats.

Lesson 9 key questions and answers

Q: What are effective strategies for strengthening market position once leadership is achieved?

A: Leverage scale to out-invest, increase switching costs with data and integrations, and become the platform for industry collaboration through APIs and third-party ecosystems.

Lesson 10: Smart vertical software CEOs (re)position their business for multiple exit paths.

Not all software companies are destined for IPO. As a CEO, you need to regularly take stock and work backwards from your desired path.

IPO: The IPO path requires hyper-growth at scale. You need to be at $100 million+ of recurring revenue and growing over 30% at a minimum. You need a massive TAM that can support a plan that gets you to hundreds of millions in ARR after the IPO so that buyers in the IPO see a credible opportunity to make a big return.

For most companies, this proves to be a tall order. Fewer than 30 vertical software companies have gone public in the past decade. Most simply do not have the growth rate or market size to support the IPO path.

There is no shame in getting off the IPO and steering your business toward a more viable exit strategy. There is nothing worse than burning lots of capital in a reckless attempt to maintain hyper-growth only to find that you’re pushing on a string.

Strategic Exit: Once you’re off the IPO path, your best bet is to position your business for acquisition by a strategic acquirer.

This involves a few key steps:

- Identify potential buyers.

- Build relationships with the CEO or P&L owner at those buyers.

- Emphasize your strategic value.

Identify buyers: Identify the companies active in your market or those who may enter your market in the future. Get connected to their CEOs through your investors or advisors under the guise of a potential GTM partnership or informal conversation.

Build personal relationships with the individuals most likely to champion an acquisition (ideally the acquirer’s CEO). Invest time in these relationships. Acquisitions are made by people, not by companies. You need to convince a CEO or P&L owner that you are the strategic solution to their problems.

Strategic value goes beyond financial value. It is driven either by competitive dynamics or a transformative growth opportunity. When building relationships with potential acquirers help them understand:

— How you can help them beat the competition

— How you can help them earn more money from their existing customers

— How you can help them enter an adjacent market and unlock dramatic growth in their business

Invest in the relationships. Do not hire a banker to put up a “for sale” sign. Instead, wait for one of the strategic acquirers to lean in with an offer. Once they do, you can hire a banker and use the inbound interest to catalyze conversations with other buyers to create a competitive dynamic.

Private Equity Exit: When you’re ready to exit, you should position for a private equity buyer while cultivating your strategic options. This way you have the luxury of both options. In recent years, there have been situations where PE buyers have been even higher multiples than strategics.

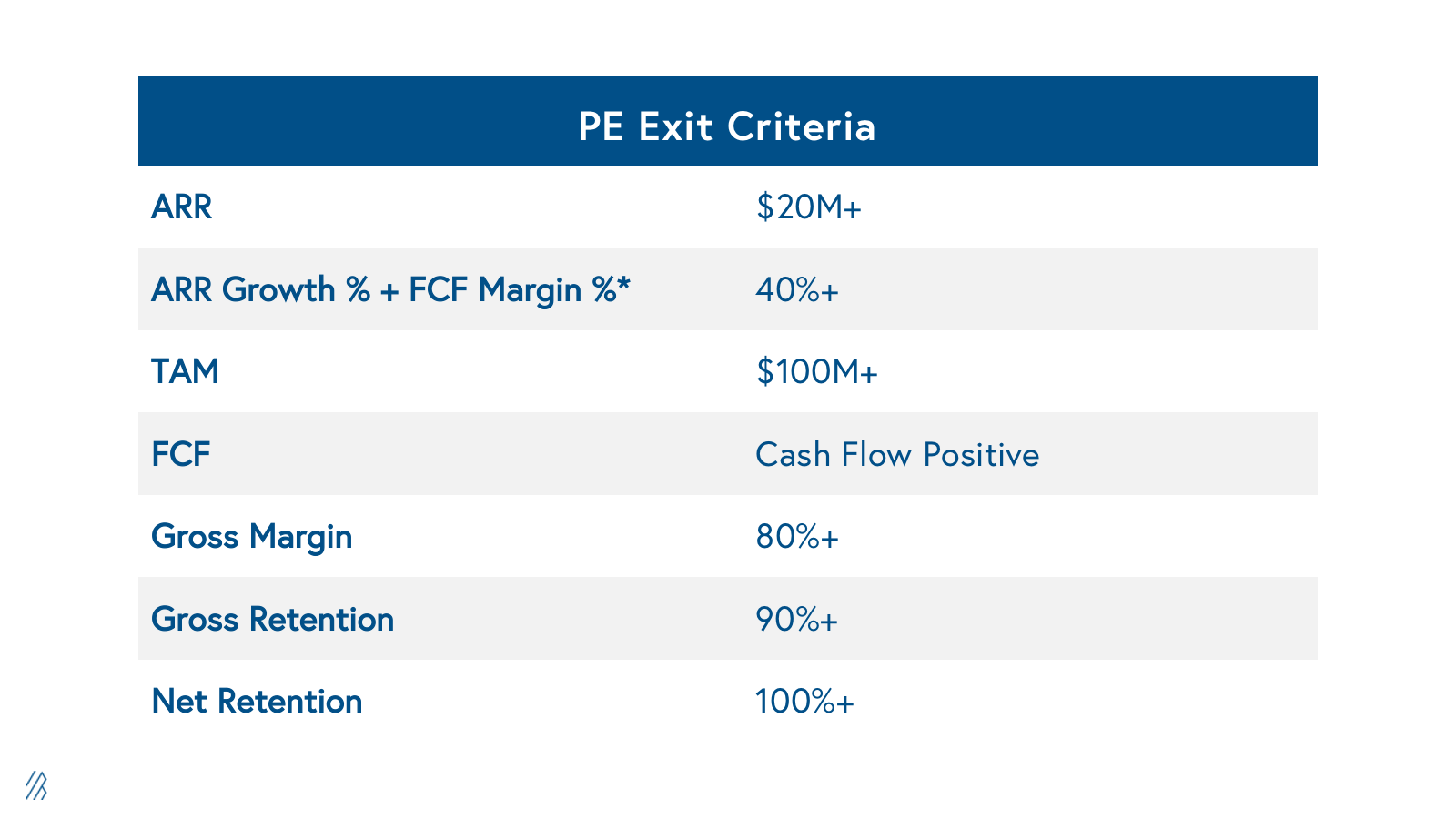

PE buyers are exclusively motivated by financial value and look at a specific set of metrics in a software business. To maximize value in a PE exit, you need to optimize for the following metrics:

- Attain as much growth and profitability as possible: The sum of a company’s revenue growth and FCF margin should be as high as possible (ideally above 40 which is often called the “rule of 40”). A company should be cash-flow positive as most PE buyers won’t touch businesses that are burning cash.

- Achieve high gross and net dollar retention: Gross retention should ideally be above 90% and your net retention should be above 100%. PE buyers and the lenders that fuel them are focused on gross dollar retention because it gives them confidence in the stability of your revenue and long-term profitability of your business.

- Demonstrate attractive sales economics: Your CAC payback should ideally be under 24 months and driven by a scalable and repeatable sales engine.

- Maintain high gross margins: Ideally above 80%. PE buyers want to achieve high levels of profitability when growth slows which is largely driven by your gross margin.

- Unlock future growth vectors: PE buyers will pay a higher price if they are confident in future growth. Show ways that your business can sustain growth after you sell through a history of market leadership, cross-selling of new products, M&A, market expansion, and other new growth horizons. If you’ve positioned your business well, you can engage both strategic and PE buyers. By attracting as many potential bidders as possible, you can drive attractive auction dynamics and get top dollar in a competitive sale process.

If you’ve positioned your business well, you can engage both strategic and PE buyers. By attracting as many potential bidders as possible, you can drive attractive auction dynamics and get top dollar in a competitive sale process.

To attract the largest number of prospective buyers and the highest valuation, it helps to be a “rule of 40” company (ARR growth % + FCF margin % is greater than 40; the higher the better) and to show profitability (cash flow breakeven at a minimum).

Businesses that are growing and profitable command the highest multiples but at a minimum, you want to either position as a 40%+ growth company operating at breakeven (trading on a revenue multiple) or a low-growth company that is highly profitable (trading on an EBITDA multiple). A <30% growth company running at breakeven or burning cash will attract the lowest level of interest among PE buyers.* If your DNA is oriented toward growth and you’re struggling to maintain growth, hire a CEO who knows how to drive profitability and is willing to do the heavy lifting to maximize value for your team and your shareholders.

Lesson 10 key questions and answers

Q: What are the main exit options for vertical SaaS founders?

A:

- IPO — requires high revenue/growth

- Strategic acquisition — requires personal relationships and demonstrating strategic value)

- Private equity — focuses on profitability and retention metrics

Q: What metrics do PE buyers value most?

A: Growth + free cash flow margin over 40%, gross retention >90%, net retention >100%, CAC payback <24 months, and gross margin >80%

Bonus lesson: B2B payment is the newest layer cake opportunity in vertical software.

As we look to the next horizon of vertical SaaS, embedded fintech providers have made it easier for software companies to deliver innovative B2B payments and spend management products.

B2B Payments

Paper checks still account for half of B2B payment volume in the United States. Vertical software providers are uniquely positioned to digitize these payment flows online and help payors pay their vendors electronically. Given that traditional ACH and paper checks are largely seen as free, the most significant issue is how to make money from those payment flows.

We’ve seen a handful of business models emerge in B2B payments in recent years:

- Software subscription fee: Companies charge for access to their B2B payment modules through software subscription fees. Coupa, an enterprise spend management software provider, launched its B2B payment module in 2018. Coupa charges customers an annual subscription fee for the module in addition to transaction fees for each payment.

- Enhanced ACH: AvidXChange, a publicly-traded provider of AP automation software offers “enhanced ACH” in addition to its standard ACH (aka eCheck) and paper check offerings. Enhanced ACH pairs the ACH transaction with additional data such as invoice amount and vendor name and makes this data available to the receivers ERP system. AvidXChange can charge for this appended data because it makes it much easier for receiver of the funds to reconcile their incoming payments with the underlying invoice.

-

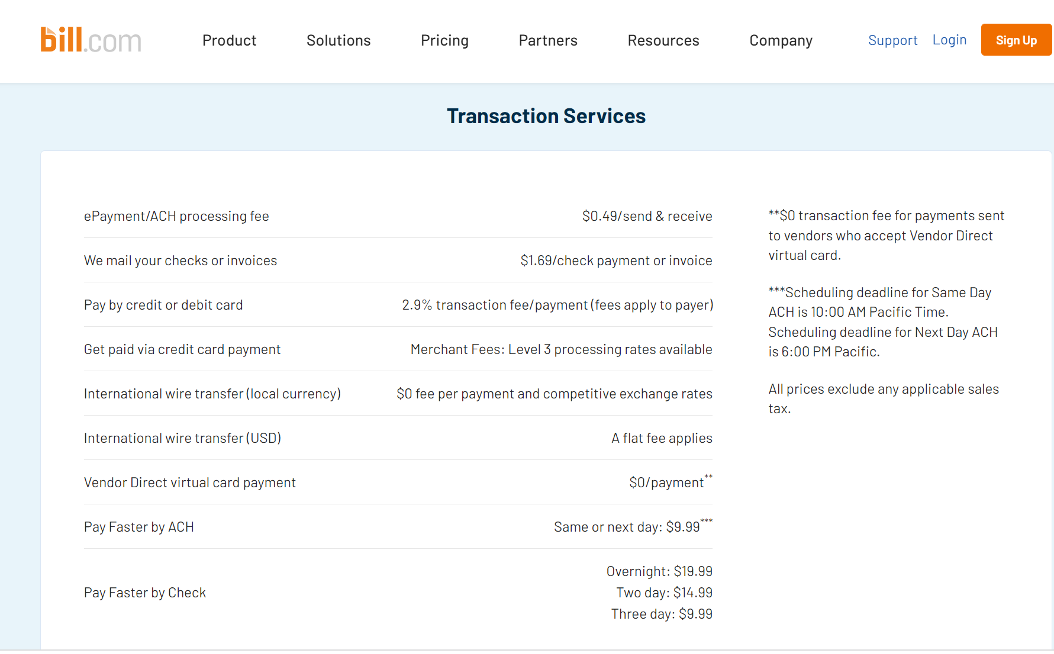

Faster payment methods: The most profitable forms of B2B payment monetization largely rely on charging for speed of payment. Faster payment options include virtual credit cards, fast ACH, and fast check. For example, AvidXChange’s most profitable payment mechanism is virtual credit card. This is a one-time virtual card that is sent via email or API to recipients of B2B payments. Fund recipients pay extra for virtual credit card (in the form of credit card processing fees) because it gives them access to the funds within 1 day rather than waiting up to 3 business days for an ACH to clear. In addition, virtual cards also entail rich remittance data and reduce the risk of fraud as compared to ACH transfers. Similarly, Bill.com offers both ‘Pay Faster by ACH’ and ‘Pay Faster by Check’ which are faster forms of traditional payments by leveraging Same Day ACH and expedited shipping of checks to deliver faster payments. Bill.com is able to charge $9.99 for faster ACH and $9.99-$19.99 for faster check.

- Cross border payments: In an increasingly global economy, companies are looking for ways to send payments to foreign counterparties and are willing to pay a premium for this service. Melio*, for example, an SMB-focused AP automation platform, charges senders a flat $20 fee per international transaction.

- Lending or early payment discounts against receivables: Companies that enable B2B payments are often able to provide value through financing options and take a cut of revenue for facilitation. Coupa Pay for example monetizes through Early Payments Discounts. In this form of financing, Coupa facilitates the matching of buyers and sellers interested in discounts offered in exchange for early payment (e.g. 5% off the invoice if the seller pays immediately rather than 30 days later) and takes a cut of this revenue from the buyer’s savings.

- Credit card payments to pay vendors: Companies, such as Melio, enable businesses to pay their bills and other expenses by using their credit card instead of ACH or check. This can be a compelling offering for SMBs that are cash constrained and stand to benefit from an additional 30 days of float (for example, if the SMB pays via credit card on day 30 of a net 30 invoice then the payment won’t be due until day 60). Melio is able to monetize these transactions by charging the sender a credit card processing fee.

Spend management

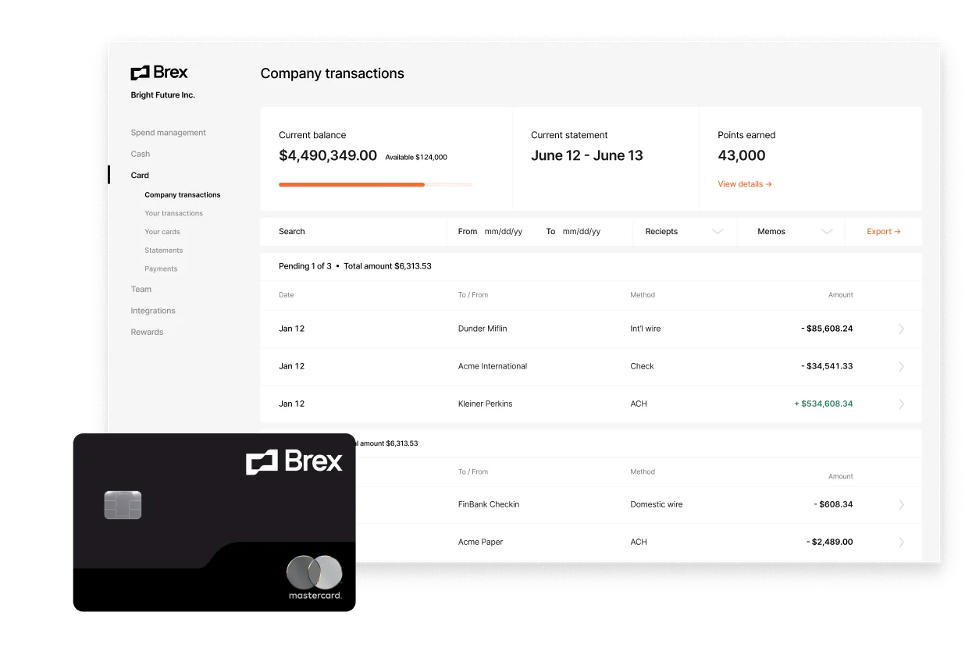

We’re also seeing a new frontier of B2B payments emerge in the form of companies like Brex, Ramp, Divvy (now part of Bill.com), etc. These combine expense management software with company-issued debit/credit cards to make it easier for their employees to pay for things.

The spend management vendors replace the traditional employee purchasing process. Rather than using purchase orders/invoices or by paying for items out of pocket and then getting reimbursed, spend management vendors arm employees with virtual and physical cards to buy things.

This can be a lucrative business model because the issuer of the card (Brex, Ramp, Divvy, etc.) captures a % of the spend on those cards ranging from 1%-3% (before processing fees). The rise of embedded card-issuing platforms like Marqeta, Lithic*, and Stripe, have made it easier than ever for software companies to issue cards to its customers.

We may see vertical-specific spend management platforms will emerge to provide software and debit/credit cards that are tailored to their end users through offerings like:

- Integrations with third-party software (for example, a construction-focused spend management provider might link each expenditure to its job cost code in the construction accounting system, which is a huge reconciliation problem for many construction firms who use a traditional expense report reimbursement process)

- Unique rewards (for example, a creator-focused solution could partner with brands and service providers to deliver unique rewards that a standard card doesn’t offer)

- Customized spend management capabilities (for example, a retail-focused spend management solution might provide dashboards that show performance by channel and let users set highly specific spending restrictions by channel based on that performance)

The opportunities in B2B payments and vertical-specific card issuing remain highly speculative. We haven't yet seen many vertical software businesses unlock the potential of B2B payments, but we expect it will inspire a new wave of opportunity in the years ahead.

Bonus lesson key questions and answers

Q: What’s the latest monetization trend in vertical SaaS?

A: Embedded B2B payments and spend management solutions, now made feasible by new fintech providers, present the next horizon in value creation for vertical software firms.

With more than a decade of investing in vertical software companies under our belts, we have grown increasingly enthusiastic about the future potential for vertical software. If you’re a founder building a software company and are raising capital or have questions about this white paper, please reach out at [brian@bvp.com](<mailto: brian@bvp.com>) and [crea@bvp.com](<mailto: crea@bvp.com>).

Ten lessons from a decade of vertical software investing was developed in part by Caty Rea and Brian Feinstein of Bessemer Venture Partners. Caty serves as Vice President at Bessemer, where she focuses on enterprise software investments across vertical SaaS, fintech, and healthcare, leveraging her experience from McKinsey & Company and other venture firms to support founders at every stage of growth. Brian, Partner at Bessemer, specializes in early and growth-stage investments in enterprise software and has played an instrumental role in leading the firm’s investments in high-profile technology companies across the globe. Both bring deep sector expertise and a passion for helping entrepreneurs build transformative businesses.

Special thanks to Trevor Neff, Mary D’Onofrio, Ethan Kurzweil, Kent Bennett, Charles Birnbaum, Connor Watumull, Ariel Sterman, and Christine Deakers for their contributions to this piece.

Appendix

*Indicates a Bessemer portfolio company